ISSN: 1941-4137

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

POETRY THAT ENACTS THE ARTISTIC AND CREATIVE PURITY OF GLASS

Amorak Huey’s fourth book of poems is Dad Jokes from Late in the Patriarchy (Sundress Publications, forthcoming 2021). Co-author with W. Todd Kaneko of the textbook Poetry: A Writer’s Guide and Anthology (Bloomsbury, 2018), Huey teaches writing at Grand Valley State University in Michigan.

Previously in Glass: A Journal of Poetry:

The Kudzu, Everywhere

September 25, 2020

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

Edited by Stephanie Kaylor

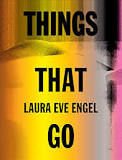

Review of Things That Go by Laura Eve Engel

Things That Go

by Laura Eve Engel

Octopus Books, 2019

The Biblical tale of Lot’s wife — who famously ignored an angel’s command not to look back at the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah and was punished by being turned into a pillar of salt — has been explored by many poets, and it’s easy to see why. In a June 2020 article in the journal Literature and Theology, Anat Koplowitz-Breier writes that for poets, “‘Looking back’ at Lot’s wife is a way of ‘re-visioning’ the biblical text that appropriates a nameless figure and seeks to revivify her, liberating her from petrification, providing her with a name and autonomous existence.” Revisiting, reframing, naming, liberating, giving voice — this is the work poems do, and this is precisely what a reader will find happening in Laura Eve Engel’s terrific collection Things That Go (Octopus Books, 2019).

Things That Go is a substantive and substantial book, checking in at 130-some pages. It’s framed by a series of poems about Lot’s wife that begin each section, centering the idea of looking carefully at the world, of being unafraid to bear witness even as the world threatens punishment. The world’s power structures benefit from the absence of scrutiny, and these poems celebrate the courage it takes to stand against that power. They also celebrate the idiosyncrasy of witness; one can observe the world only from within one’s own body:

Things That Go

by Laura Eve Engel

Octopus Books, 2019

The Biblical tale of Lot’s wife — who famously ignored an angel’s command not to look back at the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah and was punished by being turned into a pillar of salt — has been explored by many poets, and it’s easy to see why. In a June 2020 article in the journal Literature and Theology, Anat Koplowitz-Breier writes that for poets, “‘Looking back’ at Lot’s wife is a way of ‘re-visioning’ the biblical text that appropriates a nameless figure and seeks to revivify her, liberating her from petrification, providing her with a name and autonomous existence.” Revisiting, reframing, naming, liberating, giving voice — this is the work poems do, and this is precisely what a reader will find happening in Laura Eve Engel’s terrific collection Things That Go (Octopus Books, 2019).

Things That Go is a substantive and substantial book, checking in at 130-some pages. It’s framed by a series of poems about Lot’s wife that begin each section, centering the idea of looking carefully at the world, of being unafraid to bear witness even as the world threatens punishment. The world’s power structures benefit from the absence of scrutiny, and these poems celebrate the courage it takes to stand against that power. They also celebrate the idiosyncrasy of witness; one can observe the world only from within one’s own body: say I tell you

I see but what for

is a way to get at

you saw dandelions

when I said field

and meant buildings

What a lovely rendering this is of the acute sense of what is lost in translation as a poet sees the world and attempts to render it in language that is inadequate to the task. Engel expresses this disconnection not as a source of frustration but as a source of beauty.

As the title promises, the poems in this book are restless; they explore a range of landscapes from the Dead Sea desert to the Rio Grande. “I love the great American west / where the moon hunts us / for a living,” one poem offers, making explicit the analogies between the story of Lot’s wife and our current moment in history.

Serious as many of the themes may be, this is also a funny book. One poem is called, hilariously, “Look Out, Natural Disasters Are Everywhere!” A poem titled “As If in a Cave” muses on an ancient people: “Weren’t they fucking / impatient, sitting around waiting / to invent cookery, the calendar, / ships?” In another poem, the speaker swears at the moon, a line that immediately became one of my two favorite uses of the F word in a poem. (David Kirby’s “The Death of Fred Snodgrass” is the other.)

Things That Go is a beautiful book; the poems are strange and smart and full of life. These are poems about creation, about art, about building, about the things we make to interrupt the landscape: towers, billboards, cities. These are poems about paying attention, about finding beauty, about witness, about naming. These are poems full of wonder:

…It’s true too that sometimes I want

to stop looking altogether but I can’t, I’m waiting

for those moments when a city rising clearly up

out of the ground is so beautiful I think

that it must have been a part of the earth

until God or something like it shook it —

the earth — until its lesser parts just fell away.

Perhaps the most powerful move in the book comes nears its very center. A section-opening poem called Lot’s Wife ends thus: “if you outlive / the fire if you can / stand to outlive it / what will you call / yourself.” Then, the next poem is called “I Can Watch a Man in a Cage Get Burned Alive,” and it’s every bit as brutal and gripping as the title suggests.

If I can watch an orange prayer go up in a man’s body

I can never unwatch it.

A speculation about who I will be, then. After.

It’s how time works. It doesn’t stop working.

We must face not just how our observation of the world changes the world, but also how it changes us. The next poem is about the American presidential inauguration in January 2017. Suddenly, we are implicated. The meaning is clear: like Lot’s wife, we live in a moment of destruction. Will we have the courage to bear witness?

But something else happens after that: just when things seem almost to grim to bear, the book shifts. The poems get funnier. The voice grows more hopeful. The speakers are more empowered. The first poem of the final section of the book gives Lot’s wife a voice (it’s called “Lot’s Wife Speaks). The final poem in the book is a love poem to America, sort of:

Just like a brilliant inventor I too

have a body so I know everything’s invented

to pleasure a body. I was born to this country

and all of it was entranced by my tiny fingers

and then I learned where I could put them.

So, a love poem, but not a naïve one. It’s a complex, nuanced, divided love, a love that has its eyes fully open — but it’s love nonetheless, striking a final chord of hope to cap off this marvelous book of poems.

Reference

Koplowitz-Breier, Anat. ‘Turn it Over and Over’ (Avot 5:22): American Jewish Women’s Poetry on Lot’s Wife.” Literature and Theology, 34.2 (June 2020). 206–227.

Visit Laura Eve Engel's Website

Visit Octopus Books' Website

Glass: A Journal of Poetry is published monthly by Glass Poetry Press.

All contents © the author.

All contents © the author.